Bringing Pragmatism to Climate Action

- David Dodge

- Dec 20, 2025

- 8 min read

Stopping the Apocalypticism and Letting Market Forces Achieve the Energy Transition

With the election of President Donald Trump, the United States began halting action on climate change and retreating to fossil fuels, leaving some to wonder if the transition from coal, oil, and gas to renewable energy is dead. The world’s focus shifted almost overnight from concern about the impacts of climate change to anxiety about the global economy as the US president launched trade wars around the world.

Even in Canada, Prime Minister Mark Carney, known for his work on climate change, began focusing on trade relationships and “nation building” projects that emphasize fossil fuel development. The new framing has led former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair and conservative analysts to call for climate resets or a new kind of “climate realism.”

Michael Liebreich is an expert in energy transition, host of the Cleaning Up podcast, and founder of Bloomberg New Energy Finance. In his bid to take control of the “reset” narrative, he’s written two long essays in Bloomberg New Energy Finance: The Pragmatic Climate Reset – Part I and The Pragmatic Climate Reset – Part II.

Inclusive, Achievable, Affordable

He says it’s time for us to change our approach to climate change to something that’s more inclusive, has achievable goals, and is affordable and pragmatic. In his version of the climate reset, we stop demonizing people; we stop scaring people with hard-to-defend, worst-case scenarios; we end absolutism; and we adopt a plan that is achievable and, above all, affordable.

Indeed, climate change does tend to divide people into those who fear end-of-the-world scenarios and those who are simply worried about their jobs and families. Liebreich says the scary, apocalyptic scenarios are too easy to shoot down, and all-or-nothing goals, such as 100% renewable energy and bringing an abrupt end to fossil fuels, are deeply polarizing and neither pragmatic nor affordable.

Narrative Wars

“You’ve got one narrative, which is promoted heavily from the White House and the US, but also by a lot of players in the fossil fuel industry, that says the transition has failed. Nada, it’s failed, it’s over. Forget it. It was always a foolish dream. It was always childish. Look at fossils. They are 80% of [worldwide energy use] still,” says Liebreich.

“The other narrative that is out there and has carried us very far over the last few decades is that there’s a transition. The clean stuff just gets cheaper and cheaper and cheaper, and we will transition fully, and we must transition fully. And it’s incredibly scary if we don’t transition, because—and then fill in the blank of what is the latest scary story.”

Liebreich says we need to stop the political discourse that says, “If you don’t agree with the transition, you’re an evil person and you have to have your car and your boiler and your furnace confiscated.”

Has the 1.5°C Goal Perished?

“Rumors of the death of the transition have been greatly exaggerated,” Liebreich says. “And here’s why. If you believe that the transition is 1.5°, which means net zero globally by 2050, then yes, I’m afraid the transition is dead.” Indeed, in 2024, for the first time, the annual global average temperature was 1.55°C warmer.

But Liebreich says the 1.5° goal was problematic from the beginning. In fact, he exclaimed back in 2011, “Ya basta” (enough already), in effect saying, “Let’s call an end to the COP process due to its failure to deliver”—COP being the annual Conference of the Parties, which oversees climate negotiations under the 1995 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

In 2015, Liebreich ate crow when the Paris Accord was forged, which called for a goal of holding climate change to 2°C to avoid the most disastrous impacts.

The 2° goal was at least grounded in the possibility of success, but small island nations pushed back hard, with help from Canada’s then–Environment Minister Catherine McKenna. They wanted a goal of 1.5° to avoid disastrous flooding of their nations.

In the end, the Paris goal was 2°, with a compromise aspiration of 1.5°, which satisfied the island nations. But soon 1.5° became the rallying cry and the de facto goal of the world, despite no robust evidence that it could be achieved. It would have required the retirement of 45% of the fossil fuel emissions by 2030, which Liebreich says no leaders of petrostates could or would ever do—unless they were OK with economic collapse.

The 1.5° goal was an absolute make-or-break goal, driven by the possibility of real and terrible impacts, but was it achievable? This led to 10 years of work on achieving the impossible, which Liebreich says led to all sorts of important innovations and achievements. But as it turns out the premise was prohibitively costly. Analysis suggested 2° was achievable with a carbon price of $225/ton, whereas getting to 1.5° would require a price of $6,050/ton, something that just wasn’t going to happen.

The goals and the actions were driven by the very real potential impacts. But the calls for 100% renewable energy, an immediate end to the use of fossil fuels, and hard-to-defend worst-case scenarios were all part of the “absolutism” that was so deeply polarizing.

Dawn of the Pragmatic Energy Transition

“Let me say first of all, I want to make it very, very clear: What I’m not advocating for is slowing down,” says Liebreich.

Much of the criticism of the energy transition rests on a misunderstanding of what is actually being replaced. As Liebreich argues, critics rely on what he calls the “primary energy fallacy”: the assumption that renewables must somehow substitute for today’s vast levels of primary energy use. In reality, primary energy demand is a legacy accounting measure from the fossil-fuel era that includes a tracking of a huge amount of waste—especially heat lost in combustion, power generation, and transport. Clean technologies like LEDs, electric vehicles, and heat pumps deliver the same energy services—light, mobility, and comfort—using far less energy in the first place.

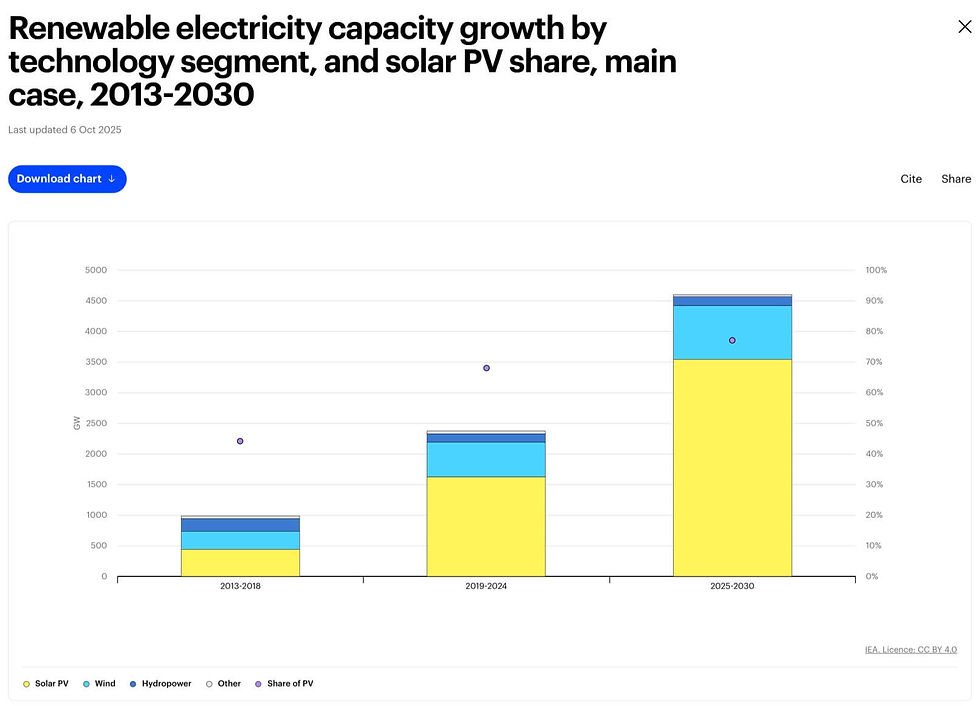

When critics cite primary energy figures to claim renewables are too small or the transition too costly, they are counting inefficiency as necessity and mistaking investments in a more efficient system for runaway costs. Liebreich says demand for energy is growing at about 3.3% a year, but that figure does not consider energy efficiency, which translates into a lower required growth rate of just 2%. And, he says, clean energy has already shown its potential for exponential growth: If we just let it grow at say 5% per year, fossil fuels will be squeezed out of the system not by 2050 but by 2065.

“I’m just saying that a much more realistic model of the transition is that the clean stuff just grows faster than demand for a very long time,” says Liebreich.

Pragmatic Growth of Clean Energy Looks Like This

Instead of simply shooting for 100% renewable energy today, Liebreich suggests, a pragmatic climate reset would mean using some natural gas and shooting for 90%–95% instead of 100%. That one small change means the transition could be quick, effective, and affordable.

How it works would be simple. Instead of using coal or combined-cycle gas plants, which are quite inflexible and lock localities into very high levels of fossil fuel usage, there would be a pivot to a new technology called flexible gas plants. (Legacy coal and gas power plants have to run constantly, wasting much energy and electricity when the demand for it isn’t there. They have to be kept running because it would take a long time to start them up or shut them down.) Liebreich points to a Finnish company called Wärtsilä Corporation that makes reciprocating (flexible) gas engines that can start and stop quickly, providing lower-emitting gas electricity during brief periods when the sun isn’t shining or the wind not blowing, thus allowing renewable energy to achieve its maximum grid input the rest of the time.

Liebreich interviewed Anders Lindberg, the president of Wärtsilä, on Liebreich’s Cleaning Up podcast. Lindberg used the real-world example of Chile, where wind and solar already generate 75% of the nation’s electricity. The other 25% comes from coal. He said that, if the coal plants were replaced with flexible gas plants, the latter would have to run for much less time than the coal facilities and would still be able to ensure that the grid received an uninterrupted supply of electricity and was kept stable.

“You would use it [the flexible gas] 4% of the time. So, you’ve gone from 25% coal to 4% gas. It’s a huge, colossal climate win,” says Liebreich.

Liebreich says fugitive natural gas emissions still need to be dealt with, and that he’s not talking about using natural gas for heating buildings, which would produce emissions nearly impossible to avoid. And besides, building heating can and will be done with heat pumps, both geoexchange and air-source heat pumps, which electrify heating very efficiently.

Isn’t a Bigger Grid More Expensive?

“Everybody thinks a bigger grid must be more expensive,” says Liebreich. But he calls electrification the “gift that keeps on giving.” As transport is electrified, a massive system of batteries is created, and as heat is electrified, thermal storage results, both which are not grid-funded resources, but on the other hand are extremely useful to the grid and grid resilience.

“So, you have this virtuous circle where the more you electrify, the cheaper the electricity gets,” says Liebreich.

The cost of the energy transition has been greatly exaggerated, he says. People may spend billions on electric cars, but that’s instead of spending billions on internal combustion vehicles. While it’s true some coal plants are being retired early, much of the so-called costs of the energy transition are actually investments by companies building a new economic future.

As Liebreich says, rumors of the death of the energy transition have been greatly exaggerated.

Seeking Highest-Probability Pathways

A transition that is fast enough to hold climate change to 1.5° may be dead, says Liebreich, but the “transition, like a tortoise, is absolutely not dead.” All clean energy needs to do is maintain an annual growth rate of 5% or more to complete the energy transition—not by 2050, but it is still possible to keep to within about 2° of global warming.

This is not, Liebreich maintains, a call for complacency: On the contrary, it’s fighting for a transition using the highest-probability pathways to success.

Speaking to the writer, Liebreich says, “You and I are of a certain age. We were never going to see net zero globally, right? Not without medical miracles. … But even if we could live in a world [with a] 95% or 90% or even an 80% clean global economy, I think we could be able to pat ourselves on the back and say, ‘Good job.’”

*David Dodge is an environmental journalist, photojournalist, and the host and producer of GreenEnergyFutures.ca, a series of microdocumentaries on clean energy, transportation, and buildings. He’s worked for newspapers and published magazines and produced more than 350 award-winning EcoFile radio programs on sustainability for CKUA Radio.

In Slither io, I hovered near a snake that kept circling nervously. Their panic made their circle tighter until they trapped themselves.